128 pages, hardcover, english

29,95€ published by GINGKO PRESS

A4 size art print included

ISBN: 9781584234173

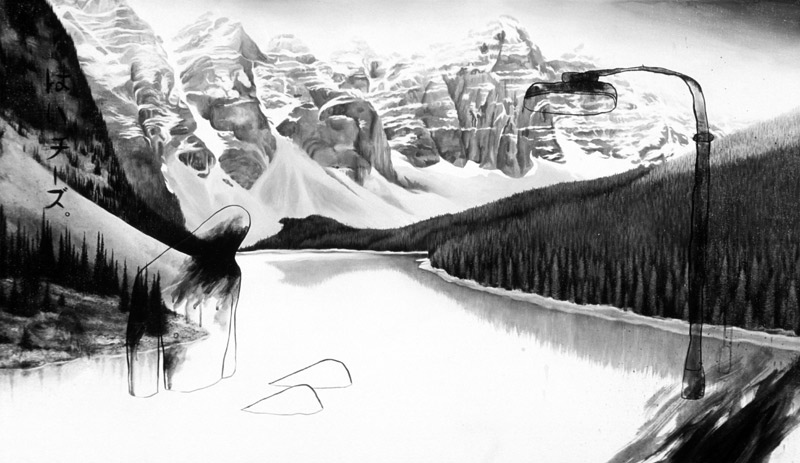

That there

That's not me

I go

Where I please

I walk through walls

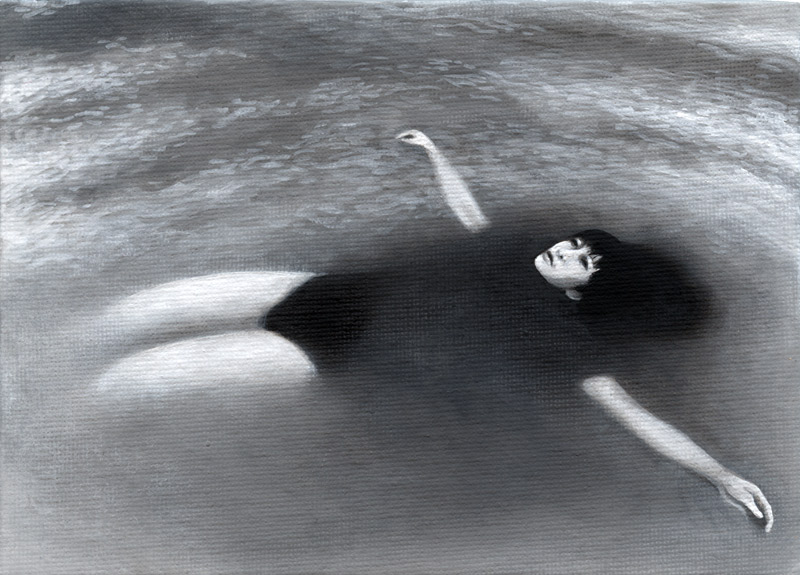

I float down the Liffey

I'm not here

This isn't happening

I'm not here

I'm not here

In a little while

I'll be gone

The moment's already passed

Yeah, it's gone

And I'm not here

This isn't happening

I'm not here

I'm not here

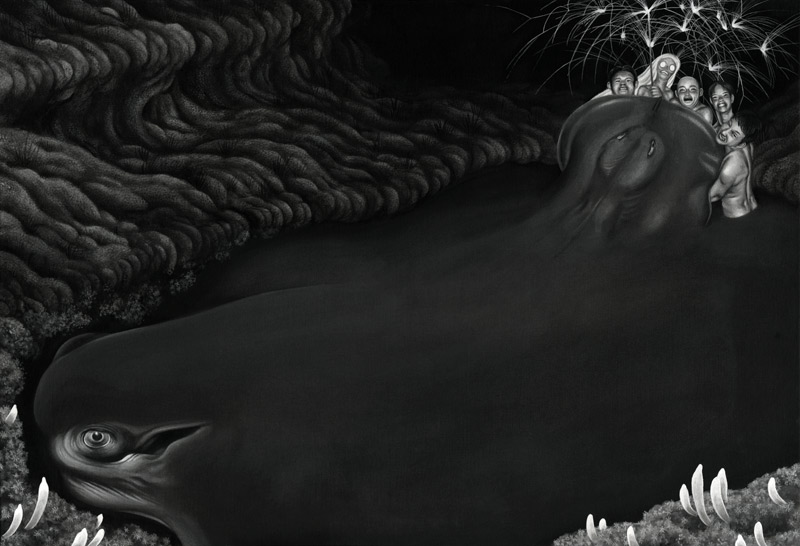

Strobe lights and blown speakers

Fireworks and hurricanes

I'm not here

This isn't happening

I'm not here

I'm not here

by RADIOHEAD

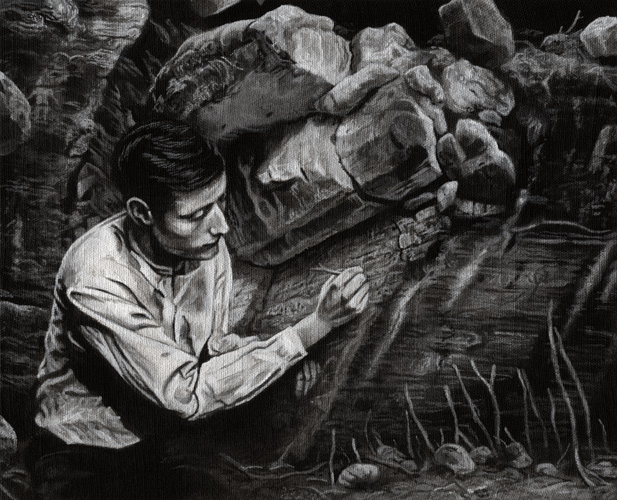

He had never experienced anything like this before [...]. It was as though he were in a different world. A million odors cascaded in on him at once - sharp, sweet, metallic, gentle, dangerous ones, as crude as cobblestones, as delicate and complex as watch mechanisms, as huge as a house and as tiny as a dust particle. The air became hard, it developed edges, surfaces, and corners, like space was filled with huge, stiff balloons, slippery pyramids, gigantic prickly crystals, and he had to push his way through it all, making his way in a dream through a junk store stuffed with ancient ugly furniture. ... It lasted a second. He opened his eyes, and everything was gone. It hadn't been a different world - it was this world turning a new, unknown side to him. This side was revealed to him for a second and then disappeared, before he had time to figure it out.

from Roadside Picnic by Boris & Arkady Strugatsky

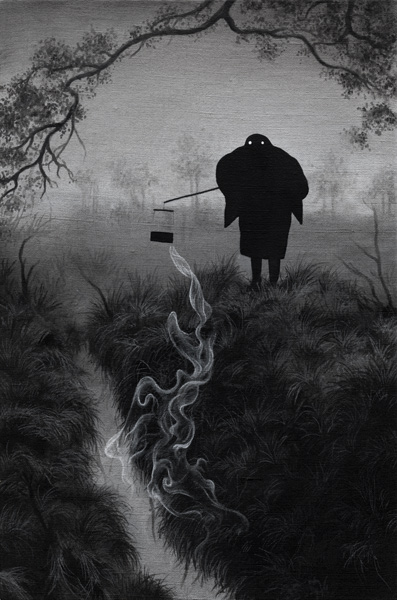

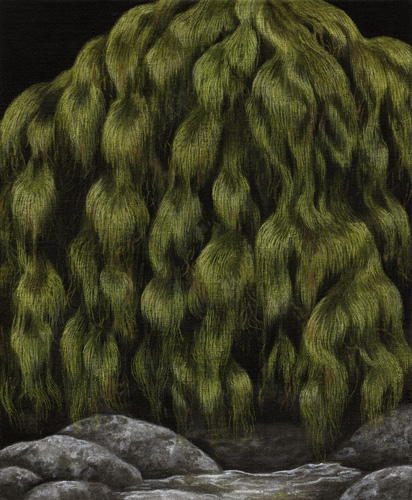

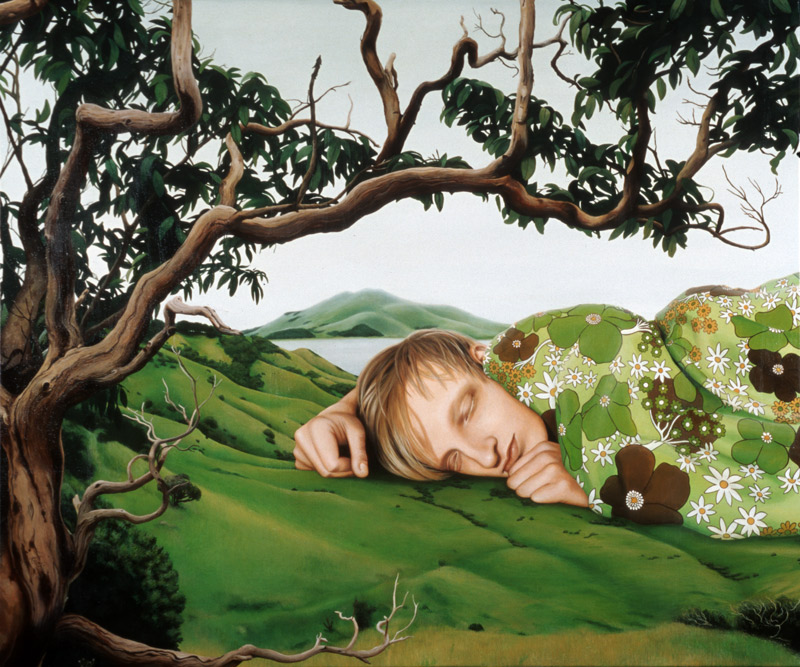

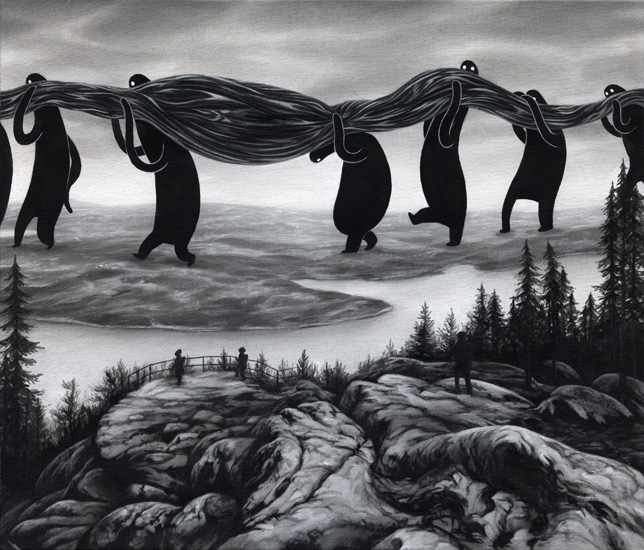

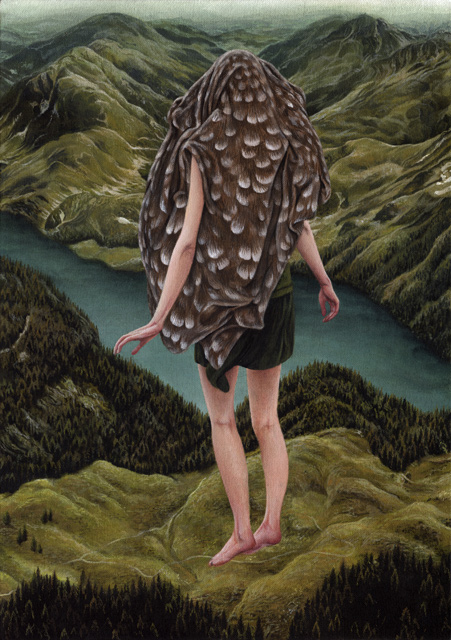

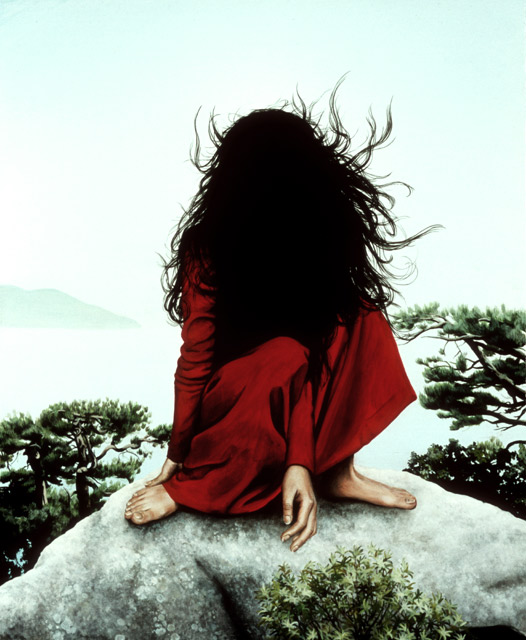

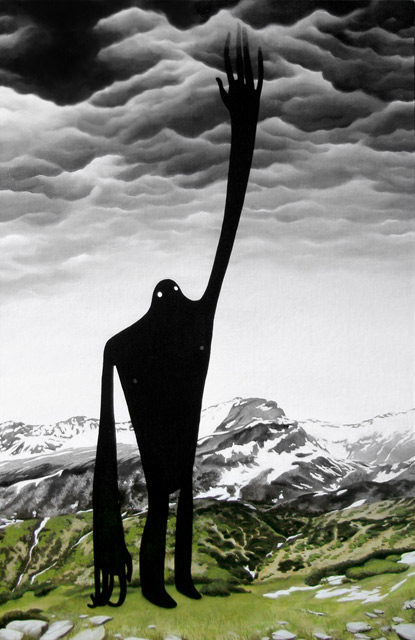

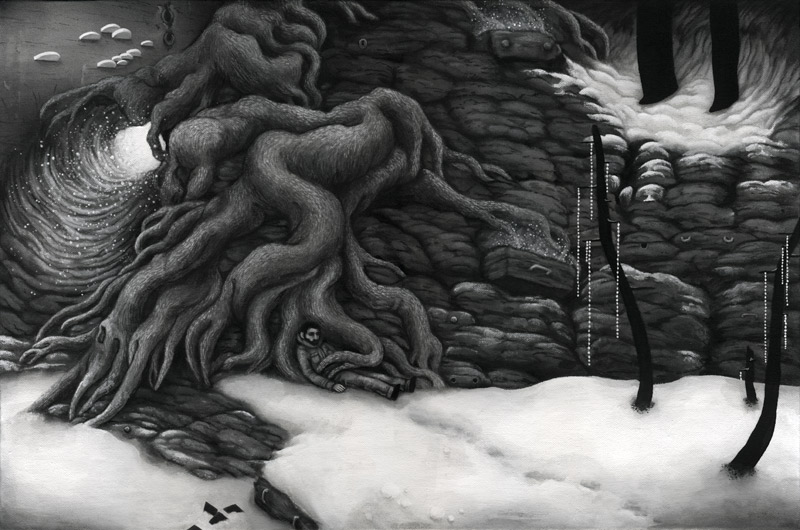

The wise one wanders where there are "no gates and no houses." He is likened to a quail, a bird that has no nest, no permanent place to stay. He "wanders like a bird and leaves no trace behind him." [...] The Japanese Master of Zen, Dôgen, also teaches the philosophy of no permanent place of abode:" "A Zen monk should be as the clouds are with no permanent place to stay; and as the water is with no firm means of support." The good wanderer leaves no trace behind him. A trace points in a definite direction. It points out the person with intent and his intentions. On the contrary, Laozi's Wanderer pursues no intention. And he is not going anywhere. He goes "without direction." He melds completely with the path which, as of itself, leads nowhere.

from Abwesen by Byung-Chul Han

Byung-Chul Han

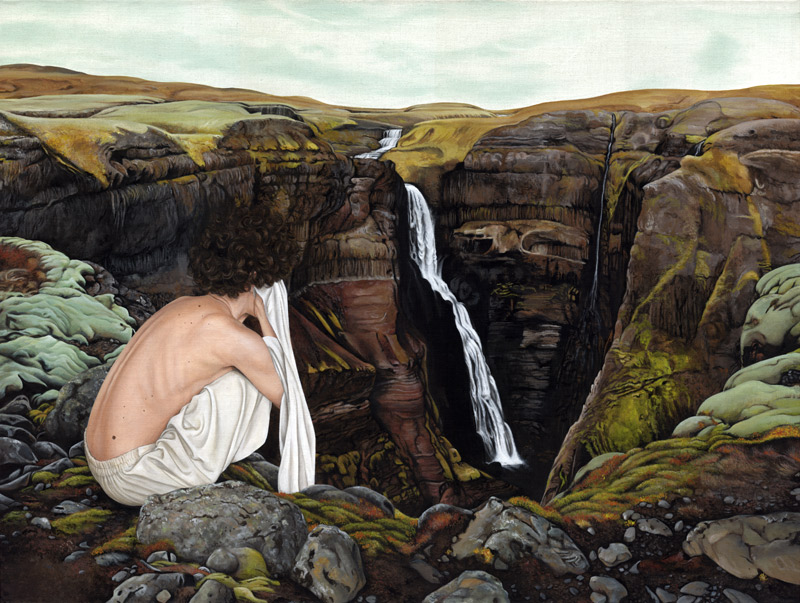

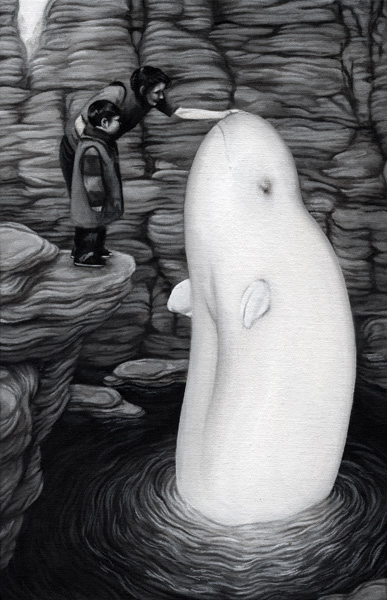

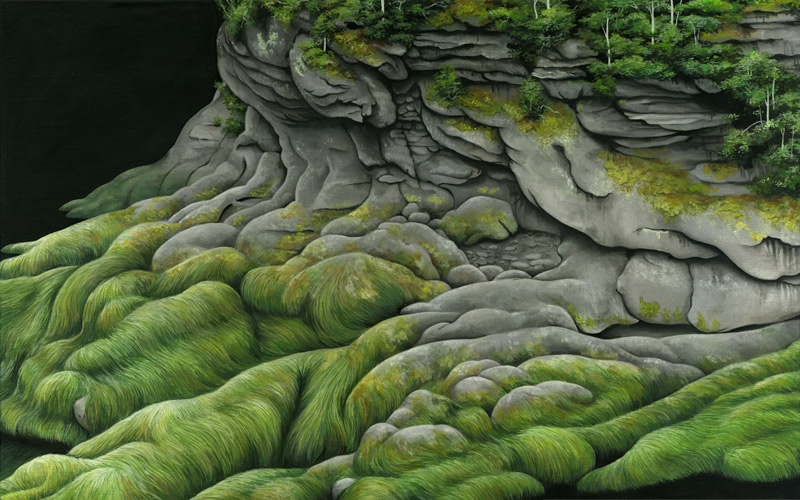

A beautiful quotation by Laozi says: A good traveler leaves no trace behind. But how can one walk and leave no trace behind? Before placing one foot on the ground you would have to raise the other, and that would be impossible. One cannot walk without touching the ground. Laozi, therefore, seems to be demanding the impossible. Or, he is asking that we float. Those who float, those who move about by floating, indeed leave no trace behind. Ghosts float too. It is well known that ghosts don't march in ordered rows with a firm step. Carl Schmitt's The Nomos of the Earth (Nomos der Erde) begins with praise for the Earth. Above all else he praises the Earth for its composition, which allows firm lines to be embedded within; and, because of its solidity it enables the establishment of clear borders, firm rules and positioning, solid framework and differentiation. The earth's solidity makes it possible for boundaries, walls, houses and fortresses to be built upon it: here the rules and positioning of man's social existence become apparent. Family, clan, tribe and societal standing, the types of possessions and the neighborhood, as well as the forms of power and rule are publicly visible. Property, possessions, power, rule, law, order and positioning all owe thanks to the Earth's unique composition. Schmitt places the Earth's fırm surface in opposition to the sea: the sea knows no such obvious entity [...] of order and location. [...] Nor does the sea allow for [...] solid lines to be embedded within. Interestingly, he then observes that the ships that travel across the sea leave no trace. The sea has no characteristic in the original sense of the word character that means embedded, carved or engraved. Due to its lack of firmness, the sea is therefore without character. And that is what enables the ocean traveler to leave no trace behind. Carl Schmitt has a phobia of the sea and of water generally. He points out a prophecy made by Virgil in which he predicted that in the coming age of good fortune there would be no more seafaring, and, that in the Apocalypse of St John he proclaimed a new world that would be cleansed of sin and in which no ocean would exist.

Carl Schmitt is a special land creature in the sense that he only thinks in firm distinctions, in dichotomous or binary opposites and has no empathy for the undecided or the indistinguishable. Existence, according to his theory, is based on clear boundaries and firm outlines, unshakeable order and principles. That is why, for him, water is so worrisome and eerie. It allows for no clear demarcation or differentiation, and on the political level no firm establishment of national or territorial borders.

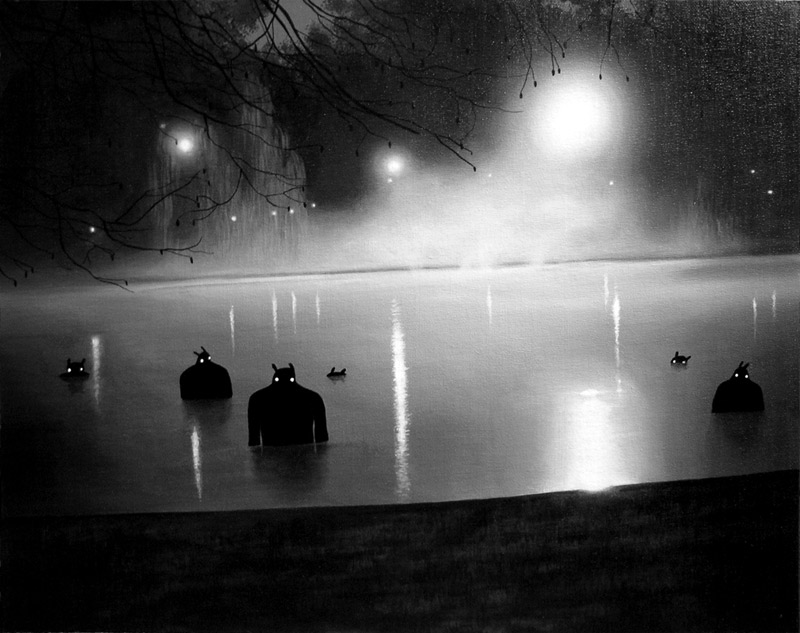

What's interesting about Carl Schmitt is that he does not naively believe in a firm order but clings to it in the face of general downfall, and attempts to build high walls on ground that has already begun to quake. Carl Schmitt thinks from within the heart of a centrifugal force that disperses firm order and diverges from its original path. He feels existentially threatened by ghostly indecision and lack of distinction. In the 1919 work Political Romanticism he summarized in dramatic language the situation in which the world found itself: constant new opportunities create a constantly new but short lived world, a world without substance [...] without strong leadership, without conclusion and without definition, without decision, without a day of final judgment, continuing indefinitely, steered only by the magic hand of chance [---] For him, a world without substance, a world without firm differentiation, without clear outlines, solid walls and barriers is a ghostly world.

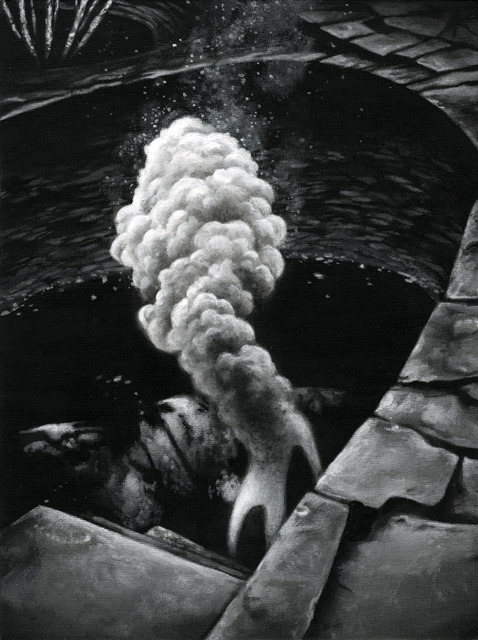

For Laozi, on the other hand, existence without strong leadership, ultimate definition and conclusion would be a leisurely stroll that would leave no trace behind. With all of his power, Carl Schmitt rejects the thought of a world without substance. Using every means possible he tries to fend off the ghostly hand of chance. In his later years, Carl Schmitt felt persecuted by voices and noises, even by ghosts. Feeling that he was at the mercy of these eerie noises he rewrote his famous sentence about supreme power: After World War I, I said "Sovereign is he who rules in the state of emergency." After World War II, in the face of death, I now say "Sovereign is he who rules the waves in space." Therefore, the sovereign individual is he who has power over ghosts. This, however, is a hopeless venture. It has been reported that Schmitt had a lifelong fear of waves. He banned both the television and radio from his room so that nothing uninvited might enter his presence. The wall, an archaic device that belongs to The Nomos of the Earth, cannot avert waves that sway in the air and evade every grasp, every boundary, every effort to link them to a specific position.

Before Schmitt, Kafka too had been greatly bothered by airwaves and electronic media. For him, these waves were ghosts that deconstructed the world and removed from it every tangibility and substantial strength - resulting in a world without substance. Even letters were ghostly forces to Kafka. In a letter to Milen; he wrote: the simple possibility of letter writing must — at least theoretically Speaking — have caused a terrible shattering of souls in the world. It is communication with ghosts [...] How could man arrive at the idea to communicate with one another through letters! One can think of those who are far away and one can touch those who are near, everything else is beyond the power of the human being. [...] Handwritten kisses don't arrive at their destination, they are sucked up by ghosts along the way. And this rich nutrition enables them to profligate. Humanity realizes this and fights against it. In order to eliminate as far as possible the ghostly between humans, and to achieve natural communication and spiritual peace, man invented the railway, the automobile, the aeroplane; but this has not helped. Obviously, it's the things invented during the course of a calamity that matter: the far side is so much calmer and stronger; after inventing the postal system it invented the telegraph, the telephone and radio technology. The ghosts won't starve but we will perish. In the meantime Kafka's ghosts have invented the internet, the cell phone and email. These are intangible methods of communication and therefore so ghostly. Without effort they transcend every border. They are able to move without any dependency on solid earth. They leap over the Nomos, the laws of the Earth and every form of geography.

Carl Schmitt too was thinking during the downfall of the old order. He negotiated his way through whole armies of ghosts. The ghosts appear when the firm framework of the old order begins to disintegrate. The more robust the order is, the noisier the ghosts become. The waves Schmitt feels persecuted by are the vibrations of decline. On the other hand, the ghosts are also messengers from beyond the wall who could possibly bring salvation. One could borrow words from Heidegger or Hölderlin and use them out of context to say: Where there is danger, salvation is also on the increase.

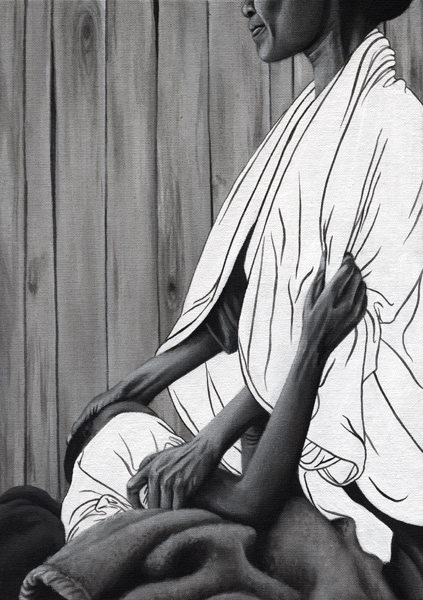

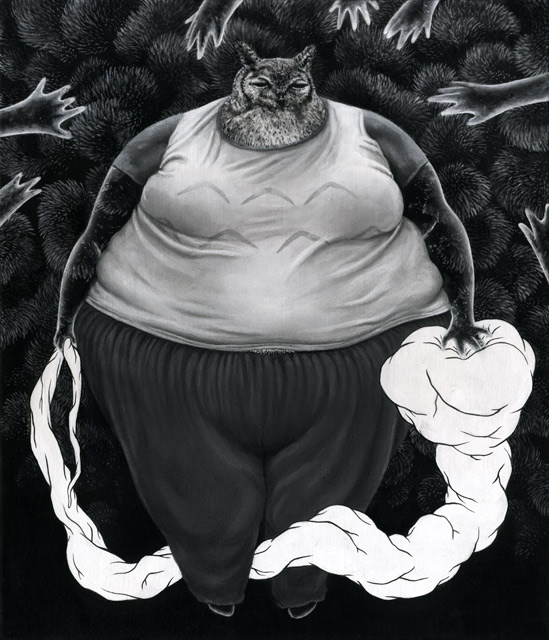

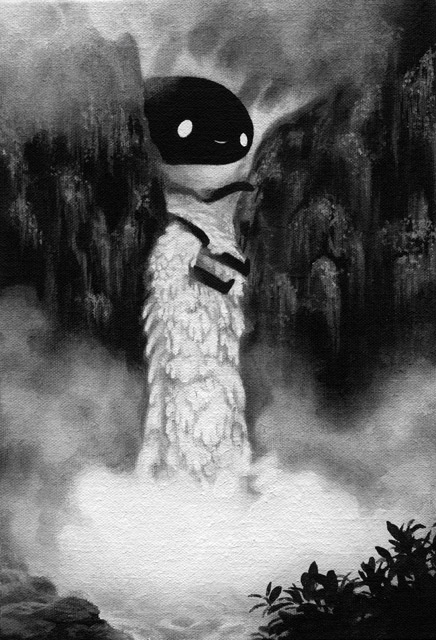

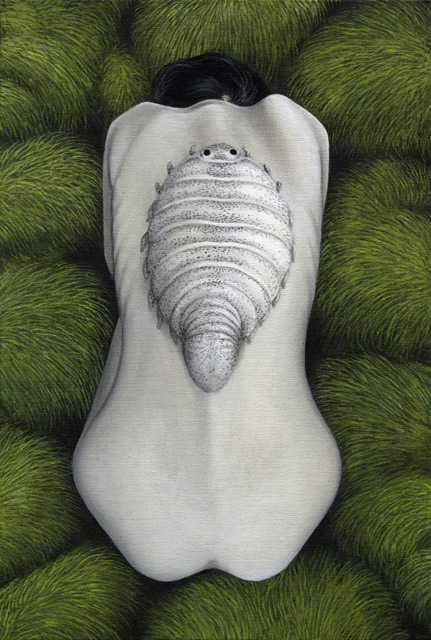

Already within its etymological origins the ghost has something contradictory or ambivalent attached to it. The word ghost (Gespenst) is related to the Old High German word spanan, which means to tempt, entice, tease or persuade. The ghost, therefore, is both tempting and alarming. One could speculate that it is so tempting because it conjures up apparitions of things that we were once prevented from seeing, things that had to be either suppressed or banned from our presence. In a sense the ghost is a revenant, a person returned from the dead, who overcomes the walls of suppression and proscription, the walls of division and exclusion. It owes its power of seduction to this revenant effect, the simultaneity of presence and absence. It succeeds in becoming an apparition, but an apparition of something that should in fact be absent. Within the syntax of the ghost there is a strong distinction between what must be and what is not permitted to be.

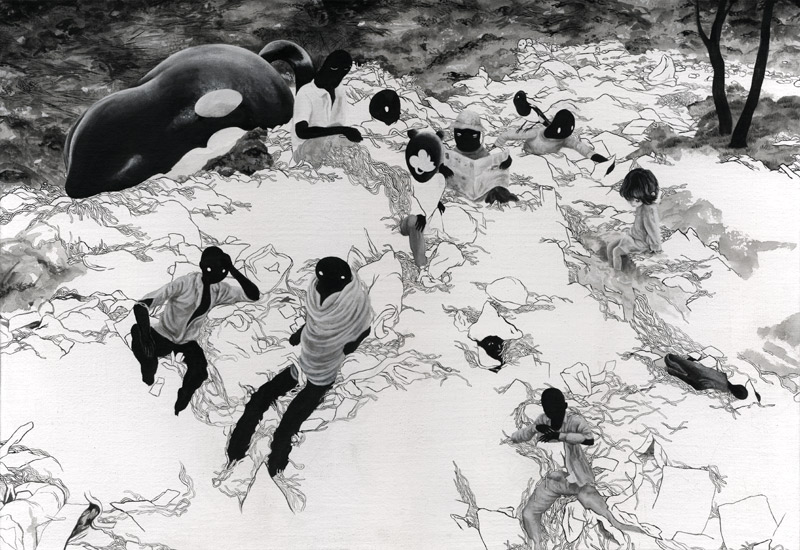

Unlike Carl Schmitt, Kafka does not use all of his power to defend himself from ghosts. He has an especially ambivalent relationship with them, a strange coexistence that often seems very amusing. Kafka's tales are haunted indeed. One can read into almost every one of his stories a ghost or something haunting. For instance, the hunter Gracchus is a ghost who wanders unhindered between life and death. As is well known, ghosts hover between life and death, between presence and absence. Interestingly, Kafka's ghosts are not frightening. They often appear as children. In the work Unhappiness he wrote: the ghost of a small child emerged from a very dark corridor in which no light had been lit, then stopped and stood on the tips of its toes [...] This ghost told the master of the house that it was only a child and therefore no fuss need be made about it. This story to demonstrates a total ambivalence towards the ghost. A strange relationship with it develops. The ghost is simultaneously rejected and accepted. In actuality the master of the house is very

frightened. But at the same time he says that he had been expecting the ghost's arrıval, and that he is really quite pleased that it has come to visit.

Kafka's most famous ghost, Odradek, in the story The Cares of a Family Man, is also embodied in the form of a child. It is implied that the small stature of the ghost would seduce people into treating it as a child. This ghost doesn't arouse any fear. In fact, occasionally one actually has the desire to speak to him. The relationship between Odradek and those around him is again ambivalent, as is the case with all of Kafka's ghosts. These specters are both disturbing and attractive. Each one of Kafka's ghosts is possessed by ambiguity.

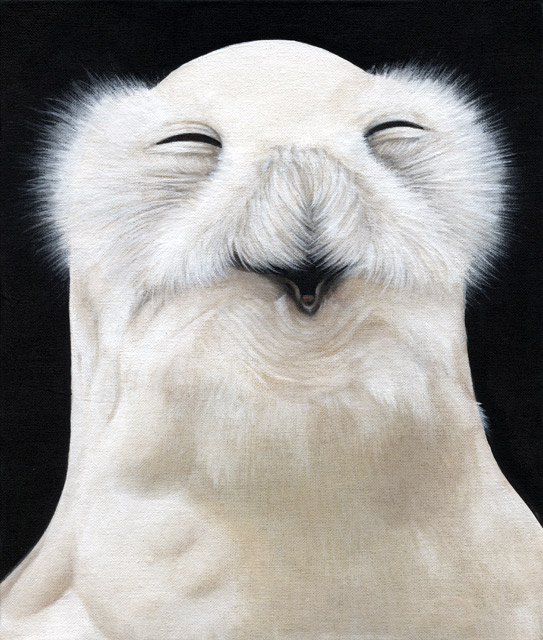

Above all Odradek is eerie because he resists all household order, all usefulness, all meaning, all theology and teleology. He represents the evacuation of meaning. But even so, he is alive, and sometimes he laughs, albeit with an eerie liveliness. He laughs in the way that one does without using the lungs. He looks broken and senseless but at the same time complete. He gives the impression of coherence, but a kind of coherence that makes no definite sense. That's why he seems so ghostly. He embodies the quintessential exception or deviation from the norm and this is exaggerated by the lack of symmetry in his appearance. Like a ghost he escapes the clutches of all. He is extraordinarily agile and cannot be caught. Above all else, he causes the father of the house concern because he has no permanent place of abode. He appears suddenly only to disappear again for months and months. But inevitably he comes back. He is a revenant.

Kafka's ghosts are not presented as totally different beings or aliens, but rather as something that possesses the character of the opponent. In the story Unhappiness the ghost speaks to the head of the house: As much as a stranger may be obliged to you, that is what I am naturally. To which the head of the house replies: You are what I am, and when | behave in a friendly manner towards you, you must do the same. In Kafka's work, however, no kindness is shown towards the ghosts. At most there is a friendly tolerance of their presence.

Zhuangzi's anecdotes often seem absurd, just as Kafka's writings do. He prefers to present characters who, like Kafka's Odradek, are anomalies. His anecdotes are peopled with the one-legged, the hunchbacked, the deformed, the toeless and footless. Like Odradek they evade any usefulness, and in fact, the law and order of the house. They pursue no goals. Nothing ties them to meaning. Zhuangzi's world appears to be without substance, without conclusion, without any firm form of differentiation or restriction. For observers who are used to a firm state of order it seems very eerie and ghostly.

Far Eastern thinking knows no unchangeable structure of order. Everything is understood in terms of change and process. There is nothing to which one could tightly cling. Which means: a good traveler leaves no trace behind. Ghosts too leave no trace behind. A trace is the imprint of compulsive holding on. Those who float leave no trace behind. In Far Eastern thinking everything is fluid. Which is why praise for water is fundamentally embodied within it. Water constantly changes its form in order to suit whatever conditions it encounters. Water knows no constraints of identity. Far Eastern thinking, due to its lack of identity constraints, affords ghosts more space. Everything is more suspended, more fluid than in the West. In greater measures everything is without threshold and transition. Boundaries and differentiations are seldom utilized. Far Eastern philosophy is not governed by 'either or,' it is governed by 'not only but also.' In contrast, Carl Schmitt, an earthly creature and land walker was an aquaphobe, afraid of water and the sea because this medium permits no clear boundaries or distinctions, no thinking in dichotomous contradictions. For him, the world that is the Far East would have been a world without substance, a world populated by ghosts. In light of such a fluid, floating world Carl Schmitt would likely have said, "In China there are only ghosts."

In the West, ghosts appear during a crisis of identity. Jacques Derrida points out that, seen from a different angle, this crisis can be liberating. His deconstruction is the science of ghosts, a form of spectrology. It investigates those elements of "otherness" that wander ghost like within the identity and put it out of balance. Damen deconstructs the make up of an identity by pointing out the things that horrify, that are dreadful, and which in the course of identity formulation are suppressed to the good of its imaginary purity. Identity, so to speak, is surrounded by the aura of ghosts. Derrida maintains a calmness towards ghosts that relieve thinking of identity constraints and identity neuroses. He pits his Logic of the Ghost against the logic of the mind, which is constantly trying to cast out the difference or otherness that rumbles within its identity. The motto of the deconstructed art of living is: Learn to live 'with' ghosts, in conversation |[...] and in shared journeys [...]' Learning to live with ghosts ultimately means: learn to be friendly, accept what makes them anomalous and unpredictable, don't passively tolerate their differences but help to propagate them. Perhaps it is possible to live more harmoniously with ghosts. With Kafka it remains very ambivalent. As the titles of his stories indicate, living with ghosts leads to Unhappiness and causes concern to the head of the household in The Cares of a Family Man. The world of Zhuangzhi or Laozi, however, is a hovering, floating world without clear outlines, without definite distinctions, without conclusions, decisions or definitions; within this world it is possible to travel leisurely through space. Perhaps in the future, on the other side of theology and teleology, floating will become the new way of walking, leaving in its wake the more rigid steps of the pilgrimage, the march, and linear forward movement.

1 Jacques Derrida, Marx' Gespenster, Frankfurt a.M. 2004, p. 10.